Henry Moves Into 18 Villa Seurat, 1934

"I am living here at the Villa Borghese," wrote Miller in 1931 while staying briefly [and free of rent] at 18 Villa Seurat, firing off the first words which would eventually form Tropic Of Cancer. In May 1934, Miller was offered to become a paying tenant--at a reduced rate of 700 francs a month--at this same house, shared with several other artist-types. Henry was excited by the idea, but also hesitant about returning to the "ghosts" of his past. [Letters To Emil, p.149]

"I am living here at the Villa Borghese," wrote Miller in 1931 while staying briefly [and free of rent] at 18 Villa Seurat, firing off the first words which would eventually form Tropic Of Cancer. In May 1934, Miller was offered to become a paying tenant--at a reduced rate of 700 francs a month--at this same house, shared with several other artist-types. Henry was excited by the idea, but also hesitant about returning to the "ghosts" of his past. [Letters To Emil, p.149]

Micheal Fraenkel was the landlord at #18. Their mutual friend Walter Lowenfels was the one to offer Miller the apartment there, supposedly on behalf of Fraenkel. Anais Nin, however, claims in her diary that she "found" the studio apartment for Henry. [Diary, 1931-1934, p.333] Regardless, the Miller biographies insinuate that Nin had a financial hand in acquiring or maintaining the pad for Henry. When actor/artist Antonin Artaud moved out of his apartment around August 1934, a vacancy opened up that allowed Henry to move in for September 1st, though he started settling in a couple of weeks beforehand with the help of Nin and others. While cleaning out a closet, Anais found a photograph of Artaud from the film La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc [the same pic at left].

When actor/artist Antonin Artaud moved out of his apartment around August 1934, a vacancy opened up that allowed Henry to move in for September 1st, though he started settling in a couple of weeks beforehand with the help of Nin and others. While cleaning out a closet, Anais found a photograph of Artaud from the film La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc [the same pic at left].

Before the official move-in date, Henry and friends had the plumbing fixed and the pillows cleaned. Pictures were hung on the freshly re-painted walls, including Miller's own watercolours and his handwritten character chart. Lowenfels was soon leaving for the States, so he let Henry have a few household basics as well as his record collection. Anais gave Henry a Victorola, a large studio rug and curtains. "Henry tremendously excited about the idea of living there. Café Alésia. Artificial geraniums. Many mirrors. Jazz. All red and white." [Diary Of Anais Nin, 1931-1934, p. 333]

Lowenfels was soon leaving for the States, so he let Henry have a few household basics as well as his record collection. Anais gave Henry a Victorola, a large studio rug and curtains. "Henry tremendously excited about the idea of living there. Café Alésia. Artificial geraniums. Many mirrors. Jazz. All red and white." [Diary Of Anais Nin, 1931-1934, p. 333]

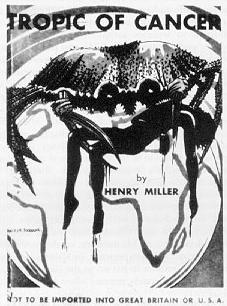

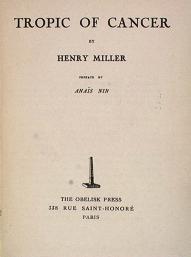

On September 1, 1934, Henry was no longer lodging at the home  of Anais Nin's mother, but had a home to call his own. That same day, Tropic Of Cancer was finally published and delivered to his door. His apartment was on the top (2nd) floor, a large studio space with a skylight, balcony/sun parlour, an old piano, and bathroom. His kitchen was cramped into a closet. The apartment was heated with steam, which did little to warm the place as the autumn descended. "The studio here is swell," Henry wrote to Emil Schnellock, "--perfect! except that it gives you neuralgia. Always a fly in the ointment. If you have light and air and space you have draughts too. And I have no covering anymore on top. No shag-pate, what! I work with a hat and shawl on." [Letters To Emil, p.157]

of Anais Nin's mother, but had a home to call his own. That same day, Tropic Of Cancer was finally published and delivered to his door. His apartment was on the top (2nd) floor, a large studio space with a skylight, balcony/sun parlour, an old piano, and bathroom. His kitchen was cramped into a closet. The apartment was heated with steam, which did little to warm the place as the autumn descended. "The studio here is swell," Henry wrote to Emil Schnellock, "--perfect! except that it gives you neuralgia. Always a fly in the ointment. If you have light and air and space you have draughts too. And I have no covering anymore on top. No shag-pate, what! I work with a hat and shawl on." [Letters To Emil, p.157]

Hearing Henry's typewriter thwacking on the other side of the wall was Arnaut de Maigret, a photographer. Hearing Henry's heels knocking against his ceiling was Michael Fraeknel, one floor below. Across from Fraenkel was Betty Ryan, whom Henry would befriend, and would be the inspiration for Miller running off to Greece in 1939.

By the end of 1934, Henry thought he was returning to America for good. Instead, Alfred Perles subletted the Villa Seurat apartment during Miller's absence, and Henry Miller returned to 18 Villa Seurat until the threat of war set him running in 1939.

A photograph of his Villa Seurat writing space can be found here.

Besides the Antonin Artaud photograph, all other images in the post are screen captures from Robert Snyder's documentary The Henry Miller Odyssey (filmed in the late 60's, when Henry returend to visit 18 Villa Seurat).

Fall 1937

Fall 1937