Witness To "Reds"

In 1979, Henry Miller was approached by actor/director Warren Beatty to appear in his film Reds, an historical love story bio-epic about social idealism in America, Communism, and the Russian Revolution. Beatty wasn't asking Henry Miller to act. His vision for his film was to include interview segments to intersperse throughout the conventional narrative structure of his story; he wanted Henry to talk about "the times" of his subjects, John Reed and Louise Bryant.

In 1979, Henry Miller was approached by actor/director Warren Beatty to appear in his film Reds, an historical love story bio-epic about social idealism in America, Communism, and the Russian Revolution. Beatty wasn't asking Henry Miller to act. His vision for his film was to include interview segments to intersperse throughout the conventional narrative structure of his story; he wanted Henry to talk about "the times" of his subjects, John Reed and Louise Bryant.In a 1979 letter to Miller, the producers requested the following: "we will be asking you about the World War I years, Emma Goldman (whom, I understand, you met), the changing sexual mores of this period, the conflict between political and artistic sensibilities."

This is part of what Miller wrote in response: "If you or Warren Beatty have read my work you must know that I dealt at length with these years. Emma Goldman, whom I met in San Diego, changed my whole life, made me elect to be a writer instead of a cowboy. I mention these things because the tone of your letter is so scholarly. I have always detested academicians [sic]. I can't talk about those years like a professor. I lived them. I was a young anarchist and now an old one...."

[ref. - PBA Galleries - The Personal Archives of Henry Miller, Pt.2 - Item# 30]

Henry agreed to be interviewed, but apparently made a condition that his young love interest at the time, Brenda Venus, appear in a future film project of Warren Beatty [this fact is found in the Dearborn biography, Happiest Man Live, p. 306, and appears to cite the letters to Irving Stettner as its primary source]. This promise remained unkept by Beatty, though Venus appears to have ended her acting career just two years later, and Beatty [at left] did not direct another film until 1990.

Henry agreed to be interviewed, but apparently made a condition that his young love interest at the time, Brenda Venus, appear in a future film project of Warren Beatty [this fact is found in the Dearborn biography, Happiest Man Live, p. 306, and appears to cite the letters to Irving Stettner as its primary source]. This promise remained unkept by Beatty, though Venus appears to have ended her acting career just two years later, and Beatty [at left] did not direct another film until 1990.The first meeting between Miller and Beatty must have been an interesting one, considering that Henry detested Bonnie & Clyde, the notoriously violent 1967 film that Beatty produced and starred in. "Bonnie & Clyde! Did I hate that!" [see Conversations with Henry Miller, p. 195]. "I feel compelled to look upon the viewers as even more sick than the killers they are watching." [from a Penthouse interview; ref.] Miller also diccusses Beatty in the Stettner book, From Your Capricorn Friend; I don't own this one, so maybe someone else can post a reference for us.

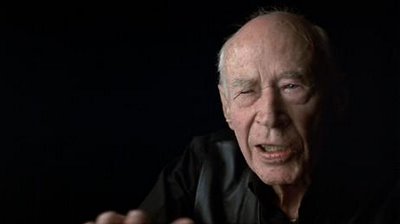

The interviewees for Reds are credited as "witnesses" but their appearances on screen are anonymous, without name titles to identify them (unless you happen to know them). Besides Miller, they included Arthur Mayer, George Jessel, Will Durant, Rebecca West, and over two-dozen others.

Reds began filming in August 1979. Miller's interview went on for 11 reels of film (acc. to Dede Allen, producer). Although Miller didn't know the two Communist subjects of the film--John Reed and Lousie Bryant--he did have a lot to say about Reed and the sexual mores of the WWI/post-WWI period. The general critical consensus is that Miller's bits are the most entertaining of the lot.

Reds began filming in August 1979. Miller's interview went on for 11 reels of film (acc. to Dede Allen, producer). Although Miller didn't know the two Communist subjects of the film--John Reed and Lousie Bryant--he did have a lot to say about Reed and the sexual mores of the WWI/post-WWI period. The general critical consensus is that Miller's bits are the most entertaining of the lot."I think that a guy who is always interested in the condition of the world and changing it, either has no problems of his own or refuses to face them." [Miller on Reed]

"People fucked back then just as much as they do now. We just didn't talk about it as much" [Miller on, well, you know]

Reds was released at the end of 1981, just in time to be considered for the Academy Awards that year (of which it was generously given). Miller would never see the film, as he died in the summer of 1980, making this likely his final appearance on film.

In celebration of the film's 25-year anniversary, the Oscar-winning Reds was finally released on DVD last week for the first time. From what I can make from internet details of its release, there are several extras on this DVD, including what I assume to be new footage of Henry Miller amongst others (I've yet to see the DVD; please confirm if you know). According to this: "One of the DVD features explores how Beatty and his staff found these individuals and used them to offer documentary-like scene-setting for the movie." I think this may be the extra titled "Testimonials," described by DVDTalk as "the story behind interviewing the Witnesses, including some raw footage."

In celebration of the film's 25-year anniversary, the Oscar-winning Reds was finally released on DVD last week for the first time. From what I can make from internet details of its release, there are several extras on this DVD, including what I assume to be new footage of Henry Miller amongst others (I've yet to see the DVD; please confirm if you know). According to this: "One of the DVD features explores how Beatty and his staff found these individuals and used them to offer documentary-like scene-setting for the movie." I think this may be the extra titled "Testimonials," described by DVDTalk as "the story behind interviewing the Witnesses, including some raw footage."See this earlier posting of mine regarding Henry Miller on film.

The film captured image of Miller in Reds was borrowed from the Tiny Revolution blog.

Miller next became aware of sexual entertainment on the advertizing found outside of a Grand Street theatre called The Unique.

Miller next became aware of sexual entertainment on the advertizing found outside of a Grand Street theatre called The Unique.

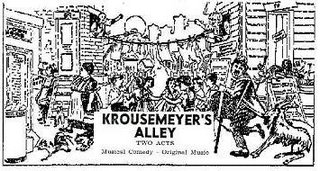

The show that the older boy from the 14th ward took Henry to see was called Krausemeyer's Alley, playing at The Empire burlesque theatre in Brooklyn. The prestigious Empire had opened about 15 years earlier, in 1893 [

The show that the older boy from the 14th ward took Henry to see was called Krausemeyer's Alley, playing at The Empire burlesque theatre in Brooklyn. The prestigious Empire had opened about 15 years earlier, in 1893 [