enry

Until A&E is prepared to have Harry Smith narrate the word "fuck," an A & E Biography about Henry Miller is not likely any time soon.

In the meantime, let's look at the modest collection of Henry's film appearances (film adaptations of his work and TV appearances will be handled later).

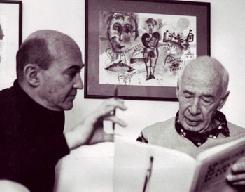

The best all-round documentary about Miller is probably Robert Snyder's

The Henry Miller Odyssey (1969). This one-hour doc has recently been issued on DVD (but still on VHS) through

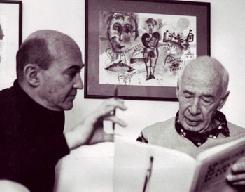

Masters And Masterworks (both graphics here belong to their website; Snyder directs Miller [below, right]).

You can view a clip of this documentary on

their Miller page. (

Quicktime)

Odyssey contains a copious amount of footage of Henry, plus interviews with Anais Nin, Alfred Perles, Lawrence Durrell and others. Henry even goes back to Paris to show us around his former haunts, don'tcha know. Great stuff.

Read

this Harvard Crimson newspaper review of the film from 1969, the year it was released.

You'll notice that the Masters & Masterworks page also contains two more Miller docs: the companion to

Odyssey, called

Henry Miller: Reflections On Writing; and something that seems to me to have been recently hauled out of the vaults,

Henry Miller Reads And Muses. Both are films by Snyder (who died, incidentally, in 2004). The latter appears to be Henry reading from

Sexus,

Tropic Of Cancer and

Black Spring, while sitting at a roll-top desk. As I haven't seen it, you can get a better description from this

cached page from the now-inactive Henry Miller Library Forum.

A couple of used VHS copies of

Odyssey with the old cover artwork still

seem to be available on Amazon.

One of Robert Snyder's assistants on

Odyssey was Tom Schiller, who later became a

Saturday Night Live writer and filmmaker. In 1973, Schiller directed

Henry Miller: Asleep And Awake (

currently available from Kultur), an intimate half-hour portrait of Henry at age 81, lounging at home (bathroom, really) and speaking freely.

This website suggests that he also apprenticed for a film called

The Life And Times Of Henry Miller (1969) [of which I know nothing]. A biography about Schiller, called

Nothing Lost Forever, contains a chapter called

Schiller And Miller. I haven't read it, but if you'd like to order it, visit

the website.

A bit of a mystery to me is the French documentary

Henry Miller, Poete Maudit, which was

screened at the Cannes Film Festival in 1974 (sorry, this last link's not worth the effort). This

German site states that it is also called

Henry Miller, Virage a 80, and was produced by Parafrance Films and directed by Michele Arnault. Lawrence Durrell also makes an appearance in this documentary.

Robert Blaisdell began making a documnetary in 1962, on the subject of Big Sur, California and the bohemian types who were drawn there. Henry Miller appears in the eventual finished product,

Big Sur: The Way It Was. The documentary was "lost" for 20 years before being remastered and released in 1994. The entire film may be viewed on its website [linked above].

Miller apparently also appears in scenes with Anais Nin in

Anais Nin Observed. I haven't seen it, however, so I can't be sure that these scenes--also directed by Robert Snyder--aren't simply taken from

Odyssey.

Finally, Miller made cameos in two motion pictures:

Tropic Of Cancer (1970) in which he is credited as 'Spectator'; and Warren Beatty's

Reds (1981) in which he appears as a 'Witness.'

An overview of Miller's film appearances can be found on-line in an

article by Jim Knipfel. The piece seems a bit sloppy, what with the actor portraying Henry in

Henry & June being referred to not as Fred Ward but as Fred

Willard ! (what a scary thought). The piece, incidenatlly, is posted on the

Blue Underground website, distributor of the 1970 film version of

Quiet Days in Clichy (you can watch a clip of the film too).

I do not personally endorse any of the companies I refer to in this posting.

Henry Miller first visited Paris in 1928. His new wife, June Mansfield, accompanied him. They stayed at the Hotel de Paris at 24 rue Bonaparte, near which is the rue Visconti.

Henry Miller first visited Paris in 1928. His new wife, June Mansfield, accompanied him. They stayed at the Hotel de Paris at 24 rue Bonaparte, near which is the rue Visconti.